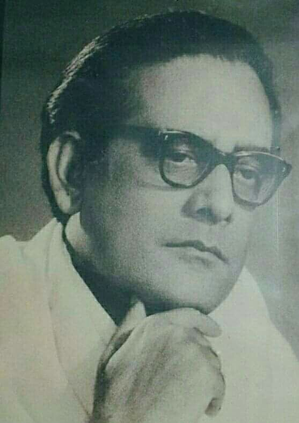

New Delhi: You should have been named Hemant Kumar because you sing so well, the tetchy heroine of the night-long caper film ‘Solva Saal’ (1958) snaps at the interloping hero after being gratuitously serenaded by him in a Bombay suburban train while she is trying to elope with her beau. This was subtle praise for the singer of ‘Hai apna dil to awara’, Hemant Kumar.

The tribute was well deserved for the singer-composer for his prowess spanned Bengali and Hindi films and whose well-modulated baritone was the voice of superstars of both industries, especially Uttam Kumar and Dev Anand. And then, he became the first Indian invited to compose for a Hollywood film – Conrad Rook’s ‘Siddharta’ (1972), based on Herman Hesse’s novel, and also used two of his Bengali songs in it.

Born on this day (June 16) in 1920 in then Benares in a family of modest means, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay was interested in music from his early years and abandoned his engineering education for music.

A rare combination of a gifted musical composer, who wove in classical strains, and a playback singer, with a gently soothing voice, he recorded his first (Bengali) song in 1940 and the first Hindi song a couple of years later.

But, while well-established in Bengali films in the 1940s, he could not make a simultaneous mark in Hindi films. It was only in the early 1950s that he was called to Bombay to give music for ‘Anand Math’ (1952), and came to national prominence for both his spirited compositions and renditions of ‘Vande Mataram’ and ‘Jai Jagdish Hare, Jai Jagdish Hare’ in it.

His next two films flopped, and a disheartened Hemant Kumar, as he had become on the suggestion of veteran filmmaker Sasadhar Mukherjee, was planning to head back to Calcutta but was convinced to stay on.

‘Nagin’ (1954), with its hypnotically compelling music, especially that snake-charmer melody on a ‘been’ – actually rendered on the clavioline by Kalyanji and on the harmonium by Ravi – both his assistants before they went to become prominent music directors in their own right – cemented his place in the Hindi film industry and also fetched a Filmfare Award for music.

But while he went on to give music – and his voice – for several other landmark films, and also went on to remake gothic literary masterpieces like ‘Bees Saal Baad’ (1962), and ‘Kohraa’ (1964), and that stark drama ‘Khamoshi’ (1969), his impact in Bombay started declining in the late 1960s as his brand of music and his genteel voice did not attract the attention it once had. However, he continued to enjoy a flourishing career in Calcutta, especially for his Rabindra Sangeet renditions, apart from films.

Hemant Kumar, who later on started to dye his hair as he contended that youngsters would not appreciate love songs from a grey-haired man, also became known for refusing a Padma Shri in the 1970s and a Padma Bhushan in the 1980s “as too late,” slowed down a bit in the 1980s due to health issues but went on. In fact, he had returned from a concert in Dhaka in September 1989 before suffering a major and fatal heart attack.

A top-notch music composer and a playback singer, like S. D. Burman, Hemant Kumar differed from the senior Burman, whose songs were more situational, more popular and enduring songs.

Take ‘Yaad kiya dil ne kahan ho tum’, picturised on a dapper Dev Anand, in ‘Patita’ (1953), or the exuberant ‘Main gareebon ka dil hoon watan ki zabaan’, from ‘Aab-e-Hayat’ (1955), which seems another of the Arabian Nights-type escapade that were once Bollywood staples, the ethereal duet ‘Nain se nain naahii milao’ in V. Shantaram’s ‘Jhanak Jhanak Paayal Baaje’ (1955), and the peppy and playful ‘Zara nazron se kah do ji nishana chuk na jaye’ (‘Bees Saal Baad’) are proof.

Then, his own composed and sung ‘Na tum hamen jaano’ from ‘Baat Ek Raat Ki’ (1962), where Dev Anand softly croons a piece of the ‘antara’, rather than the ‘mukhda’ over a sleeping Waheeda Rehman, before beginning the song.

And there was his penchant for the telling pause and change of tone – the nearly indiscernible break before ‘Bichhad gaya har saathi dekar/Pal do pal kaa saath/Kisko fursat hai jo thame deewaanon ka haath’.. and the slight change of tone for ‘Hamko apna saaya tak aqsar bezar mila…’ in ‘Jaane woh kaise log the..’ from Guru Dutt’s ‘Pyaasa’ (1957) and the voice shift in the transition from ‘… jaagte rahenge aur kitni raat ham…’ to ‘Muktsar si baat hai..’. from his Bollywood swan song ‘Tum pukaar lo, tumhara intezaar hai’ in ‘Khamoshi’.

It is no wonder why Lata Mangeshkar and Salil Choudhary dubbed him “Voice of God.”

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

–IANS

Comments are closed.