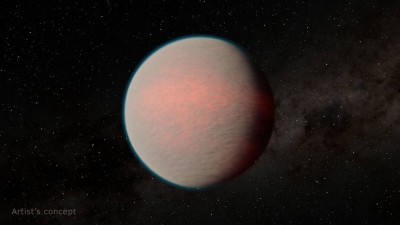

Washington: The powerful next generation James Webb Space Telescope has observed a distant planet outside our solar system — and unlike anything in it — to reveal what is likely a highly reflective world with a steamy atmosphere.

It’s the closest look yet at the mysterious world described as a “mini-Neptune”, a class of planets common in the galaxy but about which little is known. Measurements so far show they are broadly similar to, say, a downsized version of our own Neptune. Beyond that, little is known.

And while the planet, called GJ 1214 b, is too hot to harbour liquid-water oceans, water in vapourised form still could be a major part of its atmosphere.

“The planet is totally blanketed by some sort of haze or cloud layer,” said lead author Eliza Kempton, a researcher at the University of Maryland. “The atmosphere just remained totally hidden from us until this observation.”

In a paper published in Nature, she noted that, if indeed water-rich, the planet could have been a “water world”, with large amounts of watery and icy material at the time of its formation.

To penetrate such a thick barrier, the research team took a chance on a novel approach: In addition to making the standard observation — capturing the host star’s light that has filtered through the planet’s atmosphere — they tracked GJ 1214 b through nearly its entire orbit around the star with the help of the Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).

Using MIRI, the research team was able to create a kind of “heat map” of the planet as it orbited the star. The heat map revealed – just before the planet’s orbit carried it behind the star, and as it emerged on the other side — both its day and night sides, unveiling details of the atmosphere’s composition.

Kempton noted that the temperatures shifted from from 279 to 165 degrees Celsius.

Such a big shift is only possible in an atmosphere made up of heavier molecules, such as water or methane, which appear similar when observed by MIRI.

That means the atmosphere of GJ 1214 b is not composed mainly of lighter hydrogen molecules, Kempton said, which is a potentially important clue to the planet’s history and formation — and perhaps its watery start.

And while the planet is hot by human standards, it is much cooler than expected, Kempton noted. That’s because its unusually shiny atmosphere, which came as a surprise to the researchers, reflects a large fraction of the light from its parent star rather than absorbing it and growing hotter.

The new observations could open the door to deeper knowledge of a planet type shrouded in uncertainty.

Webb is an international programme led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency), and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).

–IANS

Comments are closed.