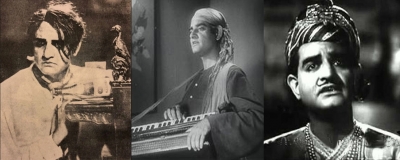

He was the first superstar of Hindi cinema – on basis of just his singing. In his short life and shorter film stint, Kundan Lal Saigal not only enthralled people across the country with his golden voice, but also made playback singing central to films, as he went on to create an abiding musical legacy that all his contemporaries as well as successors – be it Mukesh, Rafi, Talat, or Kishore – desperately wanted to emulate.

For good measure, Saigal revitalised the ghazal as popular and public form with his rendition of Ghalib, Zauq, Akbar, Arzoo and others and also went on to make recorded film music a lucrative business for music companies.

What was ironic in this that he was rejected twice by HMV in Delhi and Calcutta due to “lack of training” but went to be snapped by a perceptive agent of Hindusthan Records. One record, containing just a bandish “Jhulana jhulao re”, went on to sell a whopping five lakh pieces soon after its release in 1933!

Yet, posterity has not been very kind to him – an autodidact, without any formal training, who became a singing legend of such prowess that even classical singers were in awe of him. He also picked up Bengali so well that Rabindranath Tagore himself gave him permission to render ‘Rabindrasangeet’.

However, Saigal, if not forgotten, apart from a group of devoted aficionados (who somehow keep getting replenished), is miscast and mocked as a paragon of “old-style”, pathos-laden songs, especially his swan song “Jab dil hi toot gaya”.

A little more research might lead viewers to the upbeat and breezy “Mere Sapnon ki Rani” – where Rafi debuted as a chorus singer, from the same film “Shahjehan” (1946) – where he did not play the title role! Then, there is “Hum Apna Unhein Bana Na Sake” from “Bhanwara” (1944) where he actually laughs too.

But, then the issue is also of receptiveness – Saigal, as all those who have written on him, maintain is one who speaks to both to the listener’s head and heart and requires a mellow outlook to appreciate. He is not mere dazzle but one who slowly immerses you in the magic of his intensity and intricate art with his baritone/tenor mix with a slight nasal twang.

Born on this day (April 11 – as per a tribute to him in then leading film magazine FilmIndia after his death, though some experts say April 4 and some even April 14) in Jammu in 1904, Saigal was the son of Amarchand, a tehsildar in the service of the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir. It was from his mother Kesarbhai, who was deeply religious, that he inherited a love of music as he used to accompany her to gatherings and hear bhajans, kirtans, and shabads.

A young Saigal participated in Ramlilas in Jammu and is said to have performed in the Maharaja’s court where his rendition of Meera’s bhajans left everyone spellbound.

However, a crisis occurred when at the dawn of adolescence at 12, his voice began to crack, ending the clear soprano. His mother then took him to her Pir Salman Yousuf, who counselled the distraught youth not to lose heart, stop singing for two years, and undertake ‘zikr’ (meditation) and ‘riaz’ (practice) secretly, prophesying that this break would prove to be a “rebirth” for him.

On the other hand, his father, who had retired and moved back to the family home at Jalandhar, was not happy at his son’s dropping out of school and not taking up a proper job. Eventually, Saigal left home, taking up a variety of jobs across Lahore, Kanpur, Bareilly, Moradabad, Simla, and Delhi – as a timekeeper in the Railways, a Remington typewriter salesman, and as hotel manager, while entrancing people with his singing.

Eventually, he landed up in Calcutta in the early 1930s, where the advent of sound had revolutionised films. There are three versions of how he met New Theatres’ B.N. Sircar – with Pankaj Mullick, R.C. Boral, and a company employee cited as the conduits, while Sircar later also claimed credit.

While his initial films – debut “Mohabbat Ke Ansu” (1932) and two others did not make much waves – nor does their music survive, it was “Yahudi ki Ladki” (1933) that proved to be his first hit, while the religious themed “Puran Bhagat” (1933) and “Chandidas” (1934) made his name.

His role as “Devdas” in the epic novel’s Hindi version (1935) made him a megastar – especially with songs like “Dukh Ke Ab Din Beetat Nahin” and made a template for the character. (He also did a cameo role in the Bengali version).

Saigal was now a superstar to contend with – while the films he did the rest of the decade may not strike a chord, their songs certainly do – “Ek bangla bane nyara” (“President”, 1937), “Babul mora” (“Street Singer”,1937), “Karoon kya aas niras bhayi” (“Dushman”, 1939), “So ja Rajkumari so ja” (“Zindagi”, 1940), and “Ae qatib-e-taqdeer” and “Do naina matware tihare” (“My Sister”, 1943), among others.

Take “Mai kya janoon kya jadoo hai” (“Zindagi”) – and see how difficult it is to express the second ‘kya’.

Kanan Devi, who was a co-star, recalled that Saigal had a perfect sense for the right pitch and did not need an instrument to set it – in fact, he would sing out a note and musicians would set their instruments accordingly!

In 1941-42, Saigal, along with many others, moved to Bombay and went on to strike further milestones there right from his first film “Bhakta Surdas” (1942), known for “Madhukar Shyam hamare chor”, and then “Tansen” (1943) where “Diya Jalao” shows him as a sterling actor too – the point where he seems a bit unsure of the raga’s effect and closes his eyes mid-sentence, and then finally, “Shahjehan”.

However, his liquor habit had impacted his health – though he was not a heavy drinker and it only made his voice more mellow. His health worsened in December 1946, and he moved to hometown Jalandhar but passed away on January 18, 1947. Such was the respect he was held in that the Muslim League and others called off their agitations on the day of his last rites.

In all, Saigal acted in 36 films – 28 Hindi, 7 Bengali, and one Tamil, and sang 185 songs, including non-film, in Hindustani, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, as well as Persian and Pashto.

There are so many stories about his virtuosity, humility, and generosity, but its Naushad, his composer for ‘Shahjehan’, who penned the perfect epitaph: “Aisa koi fankar-e-mukammal nahi aaya/Naghmon ka barasta badal nahi aaya/Mausiqi ke maahir bahut aae lekin/Duniya mein koi doosra Saigal nahi aaya”.

–IANS

Comments are closed.